Triangles

| Previous - Lines | Next - Polygons |

Triangle definition

A triangle is a polygon with 3 points. The order of the points is important, as it indicates the winding order, clockwise or counter clockwise.

Triangle winding order

To know whether a given triangle A, B, C has a clockwise (cw) or counter clockwise (ccw) winding order, you can look at the sign of the cross product of AB and AC. How cw and ccw are mapped to a positive or negative cross product depends on how your cross product is defined and whether your y axis points up or down. Remember, the cross product of two vectors is the scaled sine of the angle between the vectors. When you use a mathematical coordinate system where y is up, ccw is positive and cw is negative. However in most graphical systems where y is down, cw is positive and ccw is negative.

function triangleWindingOrder(ax,ay,bx,by,cx,cy)

local abx, aby = vector(ax, ay, bx, by)

local acx, acy = vector(ax, ay, cx, cy)

local w = cross(abx, aby, acx, acy)

if w < 0.0 then

return "ccw"

else

return "cw"

end

end

Remember, this cross product is actually the z of the normal of the triangle if it was a 3d space we were working in. So the sign shows whether that normal points into or out of the plane the triangle is in.

\[(x_1, y_1, 0)\times(x_2, y_2, 0)=(0, 0, x_1*y_2-x2*y_1)\]Triangle center

Given the three points of the triangle A, B, C, we can calculate the center of the triangle as \(\frac{A+B+C}{3}\).

function triangleCenter(ax,ay,bx,by,cx,cy)

return (ax+bx+cx) / 3, (ay+by+cy) / 3

end

Triangle area

The area of the triangle is equal to half the absolute value of the cross product of the vectors originating from one of the points, thus

\[\frac{\left\lvert\vec{AB}\times\vec{AC}\right\lvert}{2}\]We will shortly show why this is so.

function triangleArea(ax,ay,bx,by,cx,cy)

local abx, aby = vector(ax, ay, bx, by)

local acx, acy = vector(ax, ay, cx, cy)

local z = cross(abx, aby, acx, acy)

return math.abs(z) * 0.5;

end

Barycentric coordinates

Concept

Every point can be written as a linear combination of the points of a triangle. The coefficients of this linear combination are called the barycentric coordinates of that point with respect to the triangle.

Lets look at a few examples. We have the triangle A, B, C. To make A from a linear combination of the points of the triangle, we can simply write

\[1*A+0*B+0*C\]So the barycentric coordinates of A are \((1, 0, 0)\).

For a point halfway between A and B, we can write

\[0.5*A+0.5*B+0*C\]So the barycentric coordinates of the halfway point between A and B are \((0.5, 0.5, 0)\). This is what we saw when we covered lines, any point between A and B can be written as

\[A+t*(B-A)\]or rewritten

\[(1-t)*A+t*B\]with t between 0 and 1. If t is not between 0 and 1, the point lies outside the line. Thus as long as the sum of the coefficients is 1, \((1-t)+t\), the point lies on the line.

Now let’s take a point which lies in the middle of the triangle. Since this point can be calculated by adding all the points and dividing the sum by 3, we can write this point as

\[\frac{1}{3}*A+\frac{1}{3}*B+\frac{1}{3}*C\]This point is called the centroid or barycenter of the triangle. Note that the sum of the coefficients is 1.

If we move the point from the center towards A, the coefficient for A will increase, while the other two coefficients, for B and C, will decrease.

Likewise if we move the center point towards the middle of A and B. The coefficients for A and B will increase while the coefficient for C will decrease.

Usage

We see that the barycentric coordinates of a point can tell us the relative distance towards each point in the triangle. They can also tell us whether a point lies within or outside the triangle as we will use shortly.

The most common place to encounter them however is triangle rendering. If you’ve ever rendered a triangle, and it had either vertex colors or was textured, barycentric coordinates where used as the weights of the color or texture coordinates. If a point P has barycentric coordinates \((a, b, c)\) so that

\[P=a*A+b*B+c*C\]and the vertices have colors \(C_1\), \(C_2\) and \(C_3\), then the color C at point P is

\[C=a*C_1+b*C_2+c*C_3\]The texture coordinates are interpolated across the triangle in the same way. In a game this can be used for more than just visual properties. If our game uses triangles to define the terrain, vertices can store for example speed factors to slow down units on certain places like sand or swamp ground. By calculating the speed factor at the unit’s position relative to the triangles points using barycentric coordinates, we can get smooth transitions between terrain types.

Calculation

function barycentricCoords(px,py,ax,ay,bx,by,cx,cy)

-- Check ABxAP relative to ABxAC

local abx, aby = vector(ax, ay, bx, by)

local acx, acy = vector(ax, ay, cx, cy)

local apx, apy = vector(ax, ay, px, py)

local denom = cross(abx, aby, acx, acy)

-- Triangle has an area of 0

if denom < 0.0001 and denom > -0.0001 then return false end

local numer = cross(abx, aby, apx, apy)

local c = numer / denom

-- Check APxAC relative to ABxAC

numer = cross(apx, apy, acx, acy)

local b = numer / denom

return 1-c-b, b, c

end

Point in triangle

Using barycentric coordinates

If we know that the barycentric coordinates are all within 0 and 1, and their sum is not greater than 1, we can say that the point is within the triangle.

function pointInTriangle(px,py,ax,ay,bx,by,cx,cy)

-- Check ABxAP relative to ABxAC

local abx, aby = vector(ax, ay, bx, by)

local acx, acy = vector(ax, ay, cx, cy)

local apx, apy = vector(ax, ay, px, py)

local denom = cross(abx, aby, acx, acy)

-- Triangle has an area of 0

if denom < 0.0001 and denom > -0.0001 then return false end

local numer = cross(abx, aby, apx, apy)

local c = numer / denom

if c < 0 or c > 1 then return false end

-- Check APxAC relative to ABxAC

numer = cross(apx, apy, acx, acy)

local b = numer / denom

if b < 0 or b > 1 then return false end

return c + b <= 1

end

Using edge tests

Another way to know whether a point p is inside a triangle is to check on which side the point lies for each edge. If the point lies on the side of the triangle for each side, it lies within the triangle.

How do we test this? Fairly simple. We take the vector AB and the vector AC and calculate the cross product. Then we do the same with AB and AP. Remember that for the cross product, the order in which we take vectors will decide the sign of the result. If we take AB x AC, we know which sign gives a point on the correct side of AB. If AB x AP matches that sign, P lies on the same side as the triangle. If we repeat this for the other two edges, we can determine whether P lies inside the triangle.

local function pointInTriangle(px,py,ax,ay,bx,by,cx,cy)

-- Check P relative to AB

local abx, aby = vector(ax, ay, bx, by)

local acx, acy = vector(ax, ay, cx, cy)

local apx, apy = vector(ax, ay, px, py)

local tside = cross(abx, aby, acx, acy)

local pside = cross(abx, aby, apx, apy)

if tside * pside < 0 then

return false

end

-- Check P relative to BC

local bcx, bcy = vector(bx, by, cx, cy)

local bpx, bpy = vector(bx, by, px, py)

pside = cross(bcx, bcy, bpx, bpy)

if tside * pside < 0 then

return false

end

-- Check P relative to CA

-- If we use AC instead of CA, our sign flips

-- but by using CPxAC instead of ACxCP our sign flips once more

local cpx, cpy = vector(cx, cy, px, py)

pside = cross(cpx, cpy, acx, acy)

if (tside * pside < 0) then

return false

end

return true

end

Of course if we know the winding order of the triangle, we can simplify this to only three cross products, as we know which sign to check for.

local function pointInTriangle(px,py,ax,ay,bx,by,cx,cy)

-- Assumes Y axis is down and triangles have clockwise winding order

local abx, aby = vector(ax, ay, bx, by)

local bcx, bcy = vector(bx, by, cx, cy)

local cax, cay = vector(cx, cy, ax, ay)

local apx, apy = vector(ax, ay, px, py)

local bpx, bpy = vector(bx, by, px, py)

local cpx, cpy = vector(cx, cy, px, py)

return cross(abx, aby, apx, apy) >= 0 &&

cross(bcx, bcy, bpx, bpy) >= 0 &&

cross(cax, cay, cpx, cpy) >= 0

end

Triangle equations

Right-angled triangle

A common, and for some dreaded, theme concerning triangles is the properties of a right-angled triangle. Given an angle and a side, calculate the remaining sides for example. However, we don’t need to learn or remember anything we haven’t covered yet.

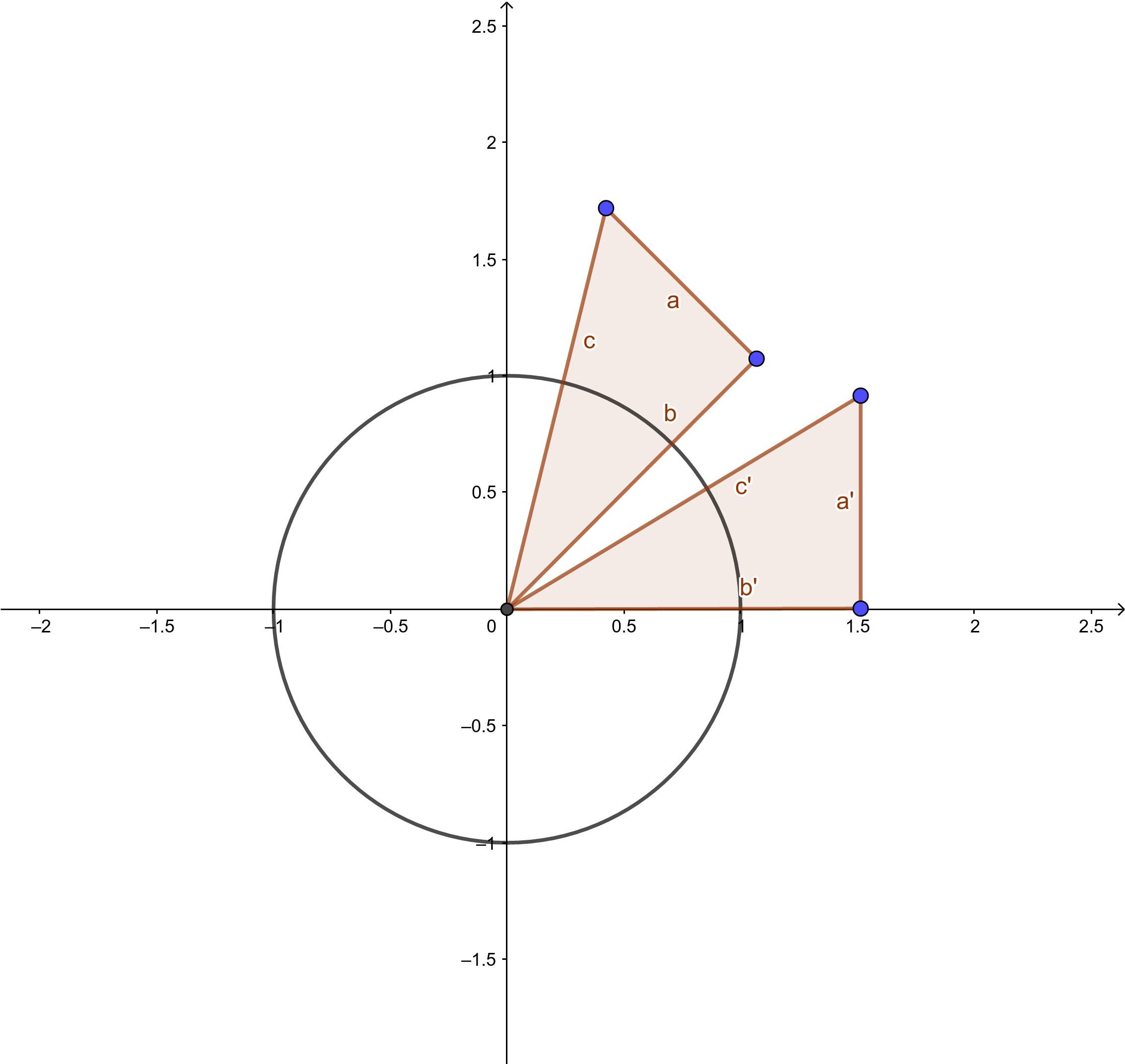

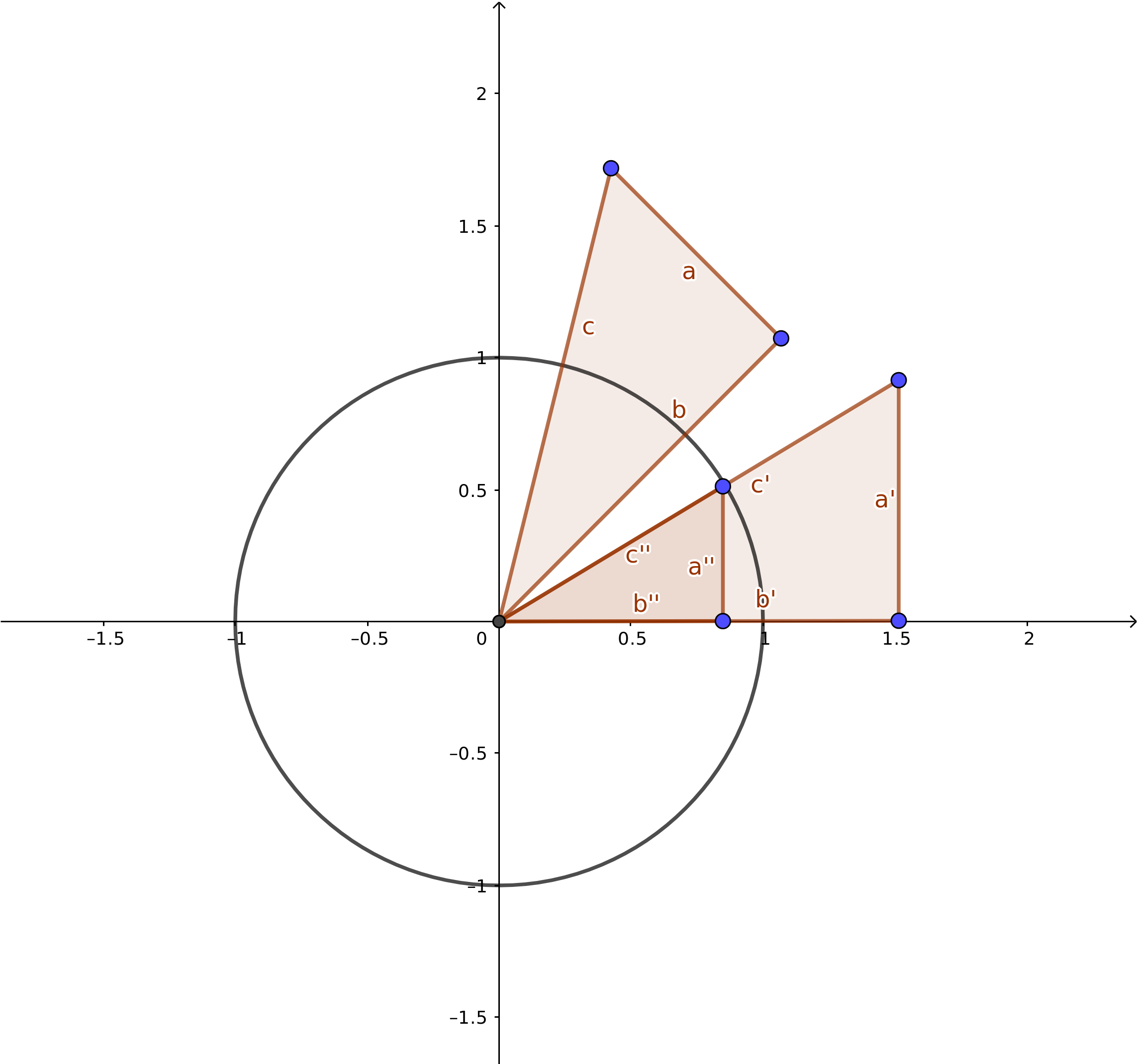

Let’s start by laying the triangle in our favorite configuration. First we rotate the triangle towards the x axis.

Then we scale it so that the length of c is 1.

We can see that if the length of c was 1, then b would be equal to the cosine, while a would be equal to the sine. Since c in most situations is not 1, we need to scale the cosine and sine by the length of c, thus

\[b=c*cos(\alpha)\\ a=c*sin(\alpha)\]That’s all there is to it. Don’t have \(\alpha\) but \(\beta\)? Just turn the triangle, or use \(\alpha=90-\beta\), since the sum of the angles is 180 degrees and one of them is 90. Don’t have c? Just divide both sides of the equation by cosine and sine respectively.

\[c=\frac{b}{cos(\alpha)} \\ c=\frac{a}{sin(\alpha)}\]Also since we know that \(cos(\alpha)^2+sin(\alpha)^2 =1\), since the dot product of the vector with itself gives us its squared length, which is equal to 1, we can write

\[c^2*cos(\alpha)^2+c^2*sin(\alpha)^2 =c^2\]by multiplying each side with \(c^2\). If we regroup the terms we get

\[(c*cos(\alpha))^2+(c*sin(\alpha))^2 =c^2\]Which gives us

\[a^2+b^2 =c^2\]Unlike learning rules, this is something you can reconstruct any time you need it.

Isosceles right angled triangle

A triangle where two sides are equal and the angle between these sides is 90 degrees might sound a bit too specialized, however it is quite common in games where objects are placed on a grid.

If we scale this triangle so that the equal sides are of length 1, the remaining side has a length of \(\sqrt{2}\).

\[c^2=1^2+1^2=2\]or

\[c = \sqrt{2}\]This means that the side of the original unscaled triangle is \(s\sqrt{2}\), with \(s\) the length of one of the equal sides.

Moreover, the distance from the point between the equal edges to the longest side is \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\).

This knowledge is useful in for example pathfinding when allowing traveling the diagonals. These diagonals are \(\sqrt{2}\) units compared to crossing both a horizontal and vertical side, which is 2 units.

General triangle

If the triangle is not right-angled, it can be split in two right-angled triangles which you can solve separately. You can use vector projection to find a point on an edge opposite to the third point and create a new edge perpendicular to the edge.

Deriving the area of a triangle formula

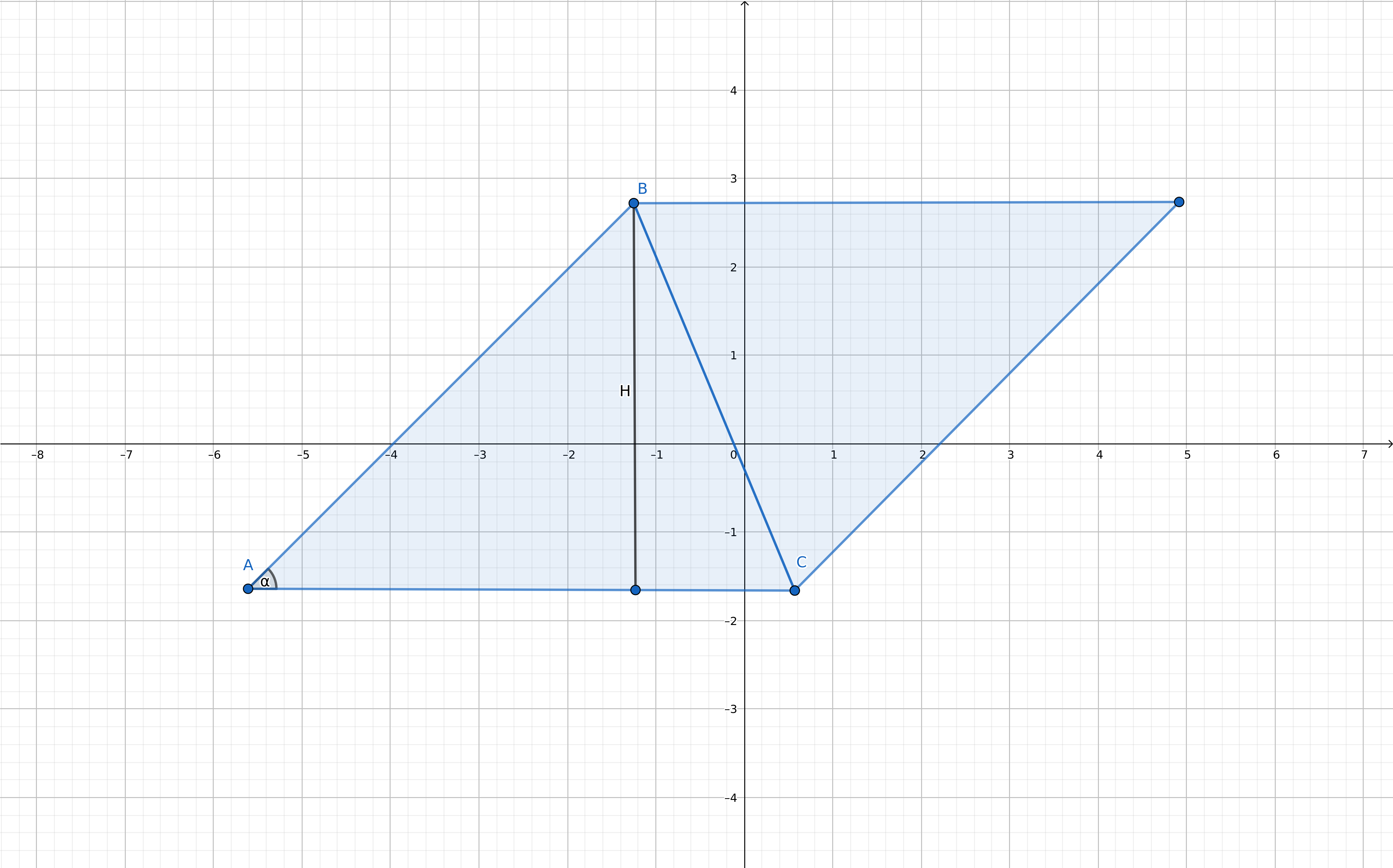

If we take the triangle, and double it across an edge, we get a parallelogram.

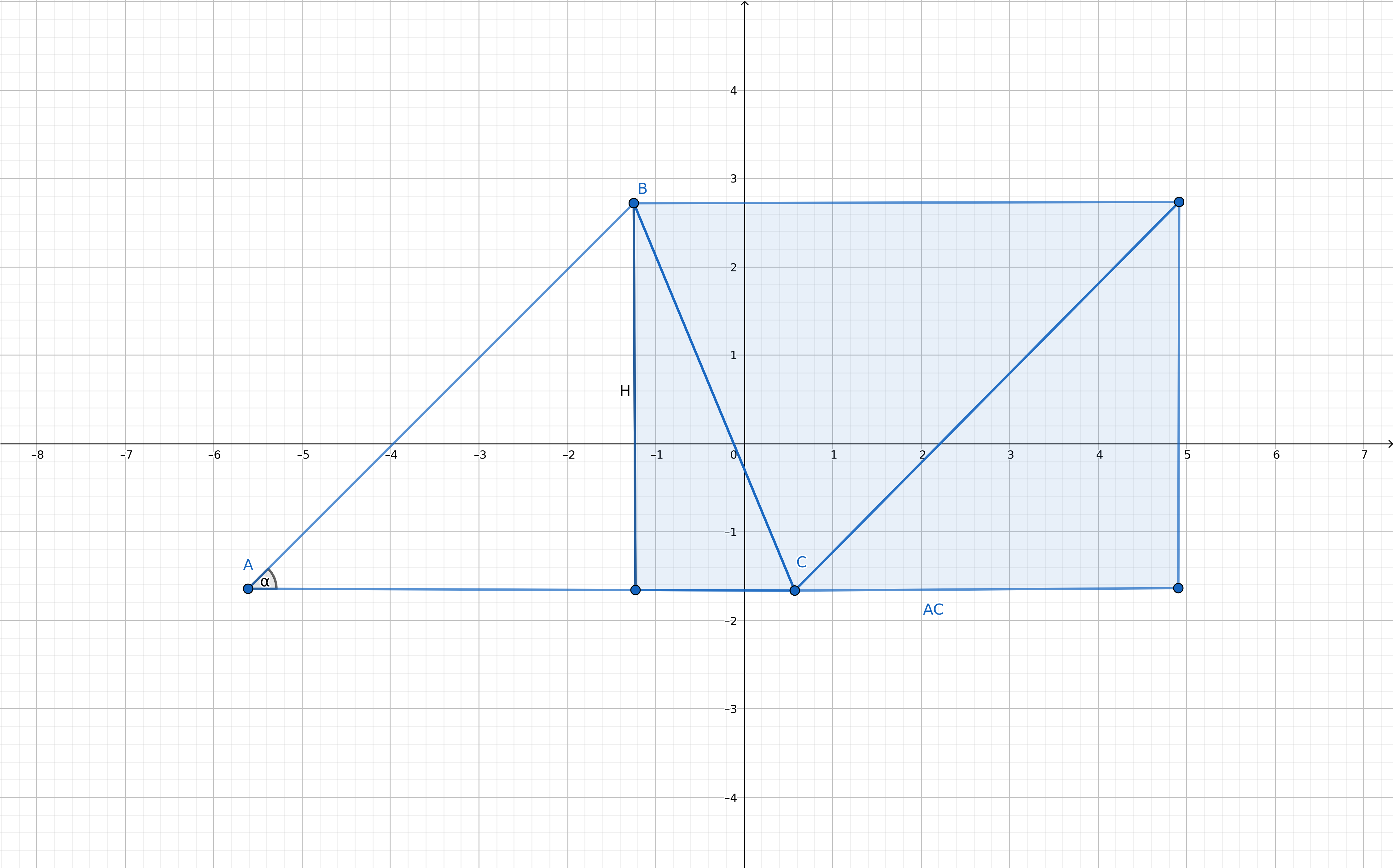

From the parallelogram, we can cut of a right angled triangle in order to construct a rectangle.

Since the area of the rectangle is width times height, thus \(\left\lVert\vec{AC}\right\lVert*H\), we can calculate the area if we have the height or H of the parallelogram. We know, since we have a right angled triangle, that

\[H=sin(\alpha)*\left\lVert\vec{AB}\right\lVert\]So the area is equal to

\[sin(\alpha)*\left\lVert\vec{AB}\right\lVert*\left\lVert\vec{AC}\right\lVert\]Remember that the cross product of two vectors is equal to the product of the lengths of the vectors multiplied by the sine of the angle between the vectors, thus

\[\vec{AB}\times\vec{AC}=sin(\alpha)*\left\lVert\vec{AB}\right\lVert*\left\lVert\vec{AC}\right\lVert\]Since the triangle is only half the parallelogram, we need to divide by two

\[\frac{\vec{AB}\times\vec{AC}}{2}\]And since a cross product’s sign depends on the order of the vectors, it might be negative depending on the triangle’s winding order, thus we need to take the absolute value

\[\frac{\left\lvert\vec{AB}\times\vec{AC}\right\lvert}{2}\]